Essay 1

PROGRAMMING LACE

Maya Gulieva

Isn’t it curious to think that a decorative language of ruffled flowers gave way to a robust and powerful language of computer programming? Running a finger over the grained underside of history like over the back of an embroidery, computing and textiles are intricately interlaced.

LACE TO LOVELACE

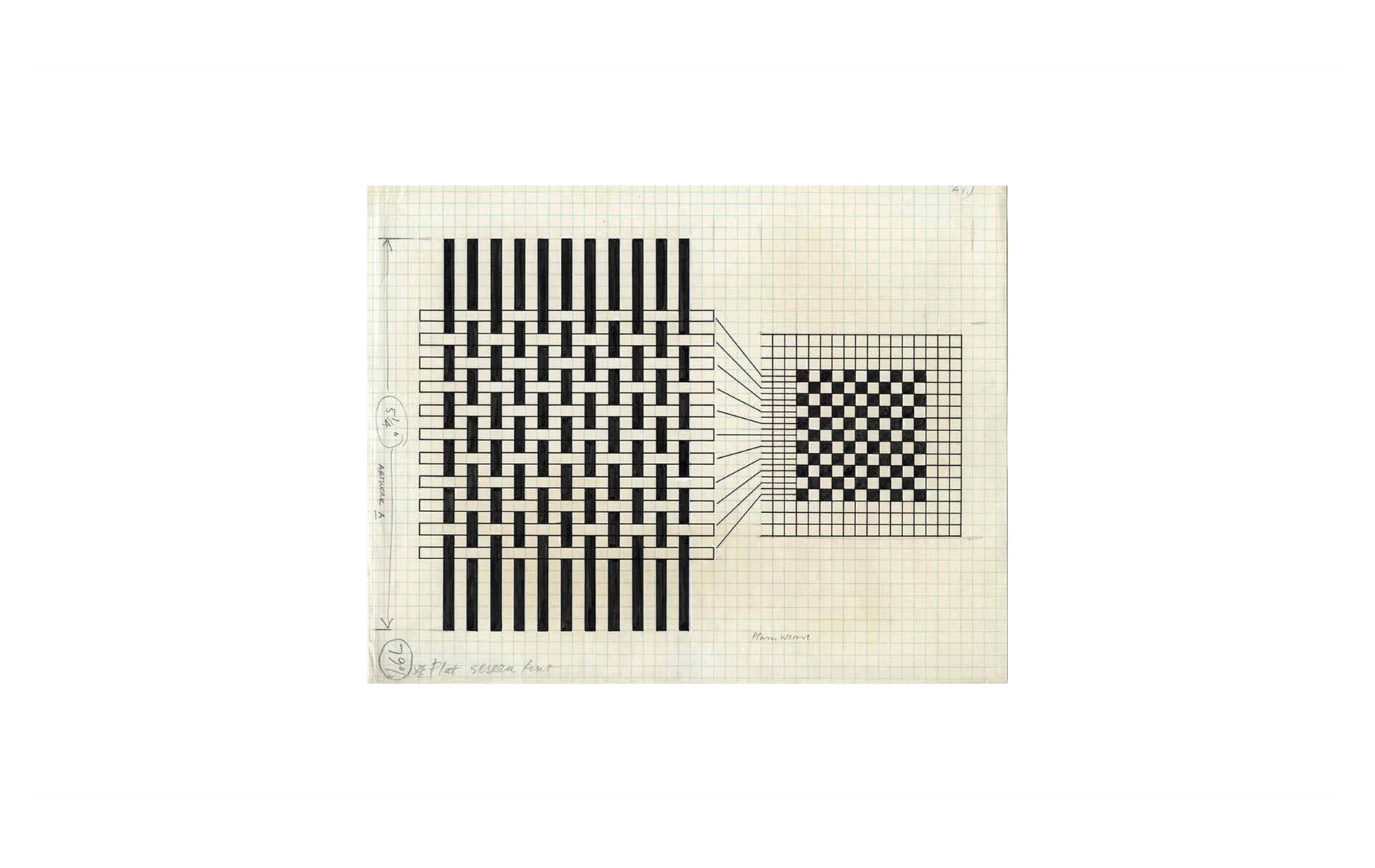

Despite its extraneous detailing, weaving, at its core, is a trade of few words: up or down. A warp thread can either be lifted up so the weft passes under and hides from view, or the warp thread is left down so the weft passes over and makes a visible mark. In 1801, Joseph Marie Jacquard programmed his punch cards to make weaving patterns with only two options: hole or no hole. Yes or no. On or off. 1 or 0. This is binary: the basis of computer programming. The same ‘holes’ that had given way to Morse Code, programmed ‘picots’ and ‘flounce’ into the sartorial pizazz of Queen Victoria and Kate Middleton, and encoded elegant authority into the jabots of Ruth B. Ginsburg. Was the answer to computing always enciphered in the visual scripts of Victorian needlework?

Lace’s cryptic glossary of flora whispered to the first computer programmer, Ada, Countess of Lovelace, who predicted the digital revolution in 1893:

We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard loom weaves flowers and leaves… the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.1

Her colleague, Charles Babbage, envisaged the Analytical Engine from Jacquard cards as instructions for mathematical calculations — instead of feeding wefts they would feed number combinations. In 1881, the first musical recorder operated “in the language of Jacquard”2 ; by 1911, the punch card holes composed data for the polynomial calculating machine and laid the foundation for IBM. Ada’s soft spoken prophecy came true in 1940, with the building of the first universal stored-program computer. Lace was the thread that spun flowers and leaves into mechanised progress.